Dawn raid. Two words that cause fear among in-house counsel, compliance officers and senior management, even more so when it occurs in a spoke location that might lack the resources and experience to manage an investigation, and where laws, regulation, business practices and/or language might differ dramatically. Taiwan, as in other Asian jurisdictions, continues to see raid activity by both financial regulators as well as prosecutors and other regulatory agencies. In their overview of investigatory raids in Taiwan, Dr George Lin and Ross Darrell Feingold of Lin & Partners discuss what internal stakeholders need to know in order to be better prepared.

Financial industry audits – past practice

The regulator for Taiwan’s banking, securities/futures brokers, insurance firms, and asset management firms (known in Taiwan as securities investment consulting enterprises (SICE) and securities investment trust companies (SITE)) is the Financial Supervisory Commission (FSC) which was established in 2004 by consolidating regulatory authorities housed in various government agencies.

The FSC’s Organic Act (as last amended June 29, 2011) grants the FSC broad investigatory authority to conduct periodic audits of business-as-usual activities, as well as ‘dawn raid’ authority when necessary.

Historically the FSC was known for periodic, and thorough, audits of financial institutions, known in Chinese as a 金融檢查, literally, financial examination. The FSC annually establishes key items that it might examine. Thus, a periodic visit by the FSC Financial Examination Bureau was expected and relatively easy to prepare for as the information and documentation demands tended to be standard. The rare sudden raids tended to be to investigate alleged violation of laws based on accusations made by current or formal staff, sat the behest of angry customers, whether institutional, high net worth, or mass wealthy who complained to the FSC following the unsuccessful resolution of a complaint and failure to satisfy the complaining customer’s compensation demands.

Financial industry raids – recent developments

What is referred to as a dawn raid in other jurisdictions is known in Taiwan as a 專案金檢, literally, sudden financial investigation. These raids have become more common in the post global financial crisis era.

One cause of this is that despite Taiwan’s lack of official diplomatic recognition, the FSC and financial instrument exchanges in Taiwan have entered into various memoranda of understanding with overseas regulators and exchanges to share information and best practices, and with certain exchanges, to allow cross-trading of products. The FSC is also an active member of the International Organisation of Securities Commissions, one of the rare examples where a Taiwan government agency participates fully in an international organisation with government agency members, including those from the mainland.

This ability to share information and learn from peers, combined with public expectations for a more aggressive regulatory posture in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, has led the FSC in recent years to shift resources from periodic audits to sudden raids. The FSC has developed extensive standard operating procedure for how to conduct a raid that seeks information with regard to specific transactions or a pattern of alleged regulatory violations.

The instigation of a sudden raid still tends to be based on accusations made by current or formal staff, or a customer complaint, though we now see that the FSC has re-allocated resources to such actions to ensure quick execution. This increases the need for better preparation. According to data publicly announced by the FSC, the number of such raids each year is now approximately double what it was two years ago.

On January 29, 2015 the FSC published on its website a list of the major items on its supervisory agenda for this year, including related party transactions, risk controls (both in local as well as overseas operations), and implementation of client protections required by Taiwan’s Financial Consumer Protection Act. Different areas of the financial industry such as the banks, mutual funds business, securities brokers and insurance firms each have a list of items specific to that sub-sector. Although the FSC may of course conduct a sudden raid based on information provided by current or former employees or angry customer, this guidance is informative as part of general preparedness actions. Although for banks, the FSC issued a separate list of items for local and the Taiwan operations of foreign banks, in our experience, multinational institutions are no more or less likely than local institutions to be raided by the FSC.

When the raid occurs

Under the Banking Act, Securities Act, Trust Enterprise Act, Financial Holding Company Act, and other laws, when FSC investigators visit a financial institution’s office locations, they have broad authority to:

- Make documentation requests: The institution may be asked to immediately provide transaction documentation, internal correspondence, external correspondence, digital records, computer network passwords, employee records and the like.

- Use facilities: The investigators may ask to use conference rooms, copy machines, and other such resources necessary to conduct their investigation.

- Interview staff: The investigators may come prepared with the names of staff they wish to interview, or, generate names in the course of their investigation. The investigators will likely seek to conduct immediate interviews.

- Open lockboxes: In an FSC investigation, materials kept in locked boxes such as office drawers or safes are not immune from investigation and a court search warrant is not required for the FSC to open same.

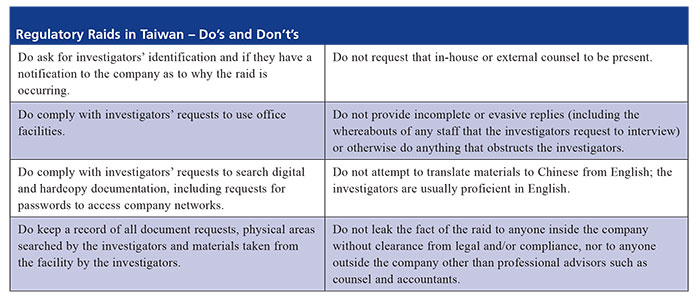

Upon the investigators’ arrival, staff may request to see the investigators’ identification. The FSC will not sign a non-disclosure or a confidentiality agreement, as they are already obligated under FSC internal rules to maintain the secrecy of the information they obtain. Responding to an FSC raid When the moment presents itself, it is acceptable to notify in-country management, regional legal and compliance or management, and if necessary alert external counsel, of the investigators’ presence. Normally the target will not ask the FSC to delay the commencement of its investigation pending such notifications. Unlike some other jurisdictions, in Taiwan it is usually a compliance officer rather than an in-house lawyer or external counsel who will be the FSC’s contact window even if the investigation is criminal rather than only administrative in nature. The involvement of legal counsel, whether in-house or external, risks unnecessarily increasing tensions. A compliance officer should ask to accompany the investigators while they search digital or hardcopy materials so as to seek compliance with the company’s privacy policy and/or the data protection laws, and may request to accompany colleagues during interviews, though the FSC has discretion whether to agree or not.

|

|

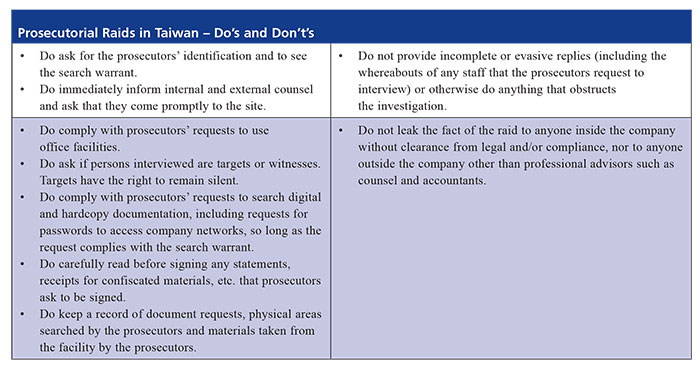

Post raid In addition to addressing any legal or regulatory violations via changes to relevant internal processes, depending on the severity of the matter, we recommend a post-raid investigation undertaken by external counsel, similar to what occurs in other jurisdictions, that would include interviews of relevant staff, review of correspondence and external counsel’s opinions and recommendations. Although a global law firm may conduct such an investigation and issue a report, unique Taiwan laws and regulations, in addition to language and cultural issues, make local counsel a more desirable option. The FSC may issue financial penalties if the institution fails to comply with its documentation and other requests. Such penalties range from NT$1.8 million (approximately US$55,000) to NT$10 million (approximately US$300,000). Typically the FSC will issue a notice with fines or request for remedial action, but will not provide the target with a detailed report of its findings, as such reports are for internal circulation only. Criminal investigations of financial institutions Raids and investigations in other regulated industries Food and pharmaceutical regulatory agencies at both the central and local government level also periodically raid corporate offices, manufacturing facilities and warehouses as part of product quality investigations. Recently the targets of such raids have tended to be local rather than multinational companies. If raided by public prosecutors, while they are on-site employees should of course request the presence of an internal of external counsel. Employees who are questioned may first ascertain whether they are being questioned as a witness or as the target of a criminal investigation. A lawyer may be present during the questioning of witnesses and targets. A lawyer may also be present to ensure that the prosecutors do not take documentation from the scene that exceeds the scope of the warrant. Taiwan’s criminal procedure code precludes the execution of a search warrant at night, subject to exceptions for urgency or the target’s consent. Where the execution of a search warrant on a financial institution or corporate might impact the stock price of a company involved in the matter, it is common for the prosecutors to execute the search warrant on a Friday afternoon so that there are two non-trading days for the market to digest the news. |

|

Attorney client privilege

The concept of attorney client privilege as it exists in common law jurisdictions does not exist in Taiwan. Thus, in a raid by a regulatory agency or prosecutors, materials such as correspondence, memoranda and the like may be read, copied and/or confiscated. There is no legal basis to deny their access to such materials regardless of what kind of wording or disclaimer is printed therein.

Conclusion

The FSC is relatively transparent in making available details about its investigatory processes, even if the raid/investigatory report is not shared with the target. The FSC also has extensive experience investigating and auditing the Taiwan offices of multinational financial institutions, and works closely with its regulatory counterparts in other jurisdictions. The trend indicates sudden raids may be more robust, or even more frequent, in the future. Financial institutions should maintain Taiwan-specific written procedures for responding to an FSC raid, and update such procedures (and staff training) periodically.

Similarly, companies operating in other highly-regulated industries should also maintain written procedures for how to respond to a raid by the prosecutors and the relevant regulatory authorities.

The authors would like to thank associate Grace Hui-Chen Lan for her assistance in the preparation of this article.

Email: attorneys@linandpartners.com.tw

Website: www.linandpartners.com.tw