By Hui Xu, Catherine Palmer, Tina Wang and Sean Wu,

Latham & Watkins LLP

E: hui.xu@lw.com

E: catherine.palmer@lw.com

E: tina.wang@lw.com

E: sean.wu@lw.com

The new law has introduced substantial changes, but certain ambiguities and uncertainties still surround it.

On November 4, 2017, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (the NPC) of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) approved and published amendments to the Anti-Unfair Competition Law (AUCL) that substantially change the previous law enacted in 1993 (the AUCL 1993). The amended AUCL (the AUCL 2018) took effect on January 1, 2018.

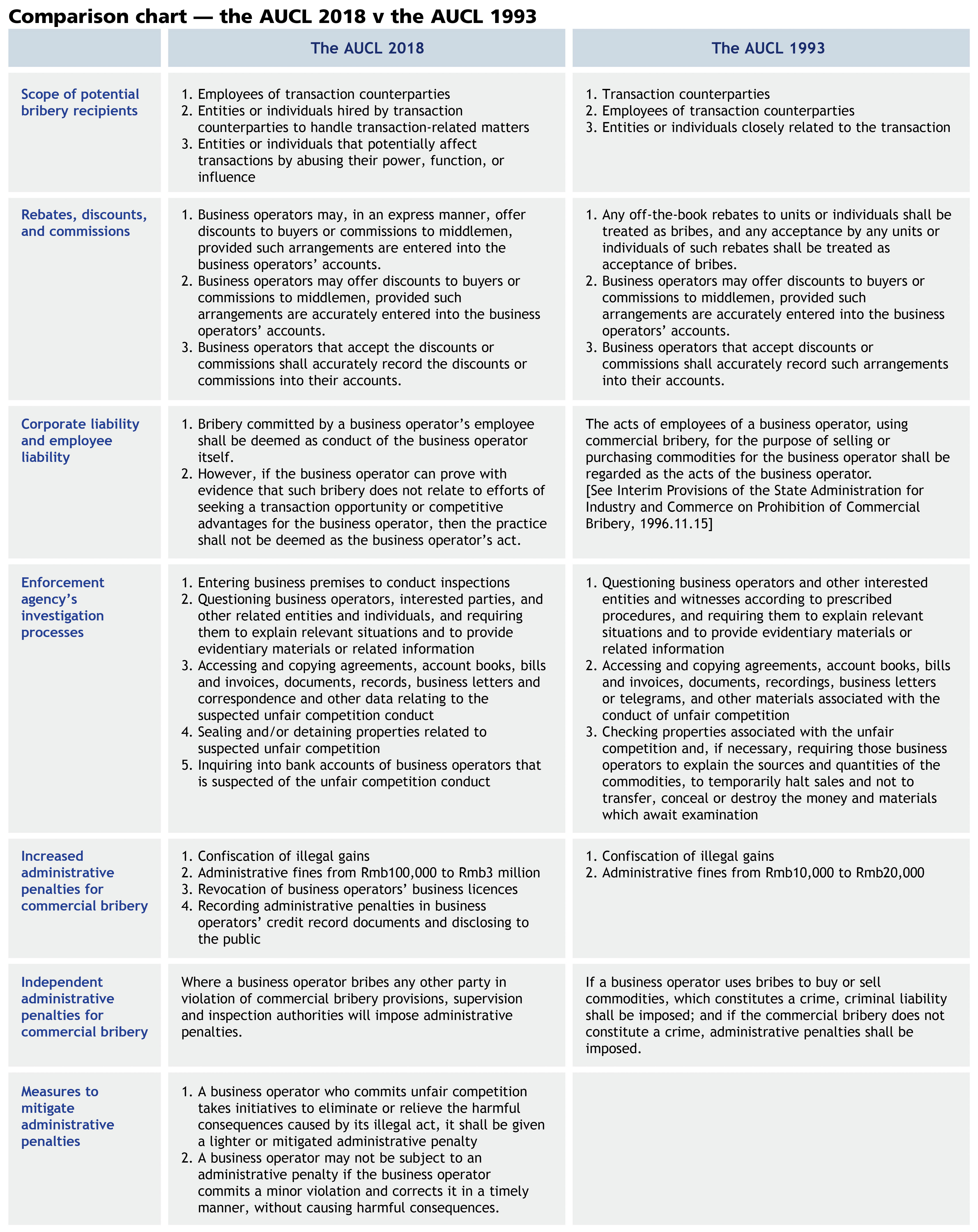

Notably, the AUCL 2018 introduced a number of significant revisions of the commercial bribery rules, including specified categories of bribe recipients, distinctions between employers’ vicarious liabilities and employees’ individual liabilities, etc.

This article summarises the key revisions introduced by the AUCL 2018, and the interpretation of “transaction counterparties”. China’s State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC), the executive branch delegated to enforce the AUCL, is expected to publish more detailed rules by way of enforcement regulations.

It is noteworthy that, as this article is about to be published, SAIC will be merged into a new central government agency called “State Administration of Market and Supervision” according to the State Council’s restructuring plan passed by the NPC on March 17, 2018.

Key features of the new commercial bribery rules

This article summarises below the key changes introduced by the AUCL 2018 to the commercial bribery rules.

Identifies three categories of commercial bribery recipients and excludes transaction counterparties as “bribe recipients”

The AUCL 2018 elaborates on the potential bribe recipients by listing three specific categories of entities and/or individuals:

- employees of transaction counterparties;

- entities or individuals hired by transaction counterparties to handle transaction-related matters; and

- entities or individuals potentially influencing transactions by abusing their power, function, or influence.

Notably, the AUCL 2018 does not include transaction counterparties themselves as a category of bribe recipients, which, in other words, shows the view of the state legislature that a payment by a business operator to a counterparty in a transaction is not commercial bribery.

Retains safe harbour provision for business operators

Similar to the AUCL 1993, the AUCL 2018 affords business operators a degree of leeway in respect of properly documented discounts and commissions. The AUCL 2018 allows a business operator to pay discounts to a counterparty, or commissions to an intermediary or agent in the course of a transaction, provided that such arrangements are transparent as well as clearly and accurately recorded. Contrary to the AUCL 1993, the AUCL 2018 apparently has deleted a sentence stating that all off-the-book rebates are treated as commercial bribery.

Clarifies corporate liability for commercial bribery

The AUCL 2018 provides that if a business operator’s employee engages in commercial bribery, the activity should be viewed as the conduct of the business operator. However, the AUCL 2018 also provides that if the operator can prove that the employee’s activity does not relate to the business operator’s obtaining of business opportunities or other competitive advantages, the business operator will not be held liable for the employee’s conduct. The burden of proof would remain on the business operator, should the business operator seek to argue no corporate liability.

Refines enforcement agency’s investigation processes regarding suspected commercial bribery

The AUCL 2018 expands enforcement agencies’ investigative powers by including, for example, the power to inspect premises, detain properties, or conduct inquiries relating to bank accounts, etc. Meanwhile the AUCL 2018 also imposes more processes and procedures on these agencies to prevent them from abusing their power and to address due process requirements, e.g., requiring agencies to produce a written report before beginning investigative measures, and to release investigation results to the public in a timely manner.

Increases administrative penalties for commercial bribery

Under the AUCL 2018, the administrative authorities are empowered to confiscate illegal gains and impose a fine of Rmb100,000-Rmb3 million (US$16,000-US$474,000), as well as to revoke a business operator’s business licence in cases of severe misconduct. In addition, the AUCL 2018 provides that if a business operator receives an administrative penalty for engaging in commercial bribery, enforcement agencies will record the penalty in the business operator’s public credit record. This would not only harm the business operator’s reputation, but also affect its credit record which usually is a key factor to be evaluated when a business operator bids in a public tender.

Emphasises independent administrative penalties for commercial bribery

The AUCL 2018 removes the phrase “not constituting a criminal offence” that the AUCL 1993 had included as a precondition of administrative penalties for commercial bribery. The removal of the phrase emphasises that administrative penalties can be imposed regardless of whether or not an act in question constitutes a crime.

Provides measures to mitigate administrative penalties for commercial bribery

The AUCL 2018 provides that business operators that have committed minor violations can mitigate administrative penalties by proactively eliminating or reducing the harm that the violations caused. While the provision does not specify the extent of harm that should be eliminated or reduced, it provides business operators with an avenue to mitigate their exposure to penalties.

The interpretations of “transaction counterparties” and potential implications FOR enforcement

One of the most discussed changes is the exclusion or omission of a “transaction counterparty” from the category of bribe recipients under Section 7 of the AUCL 2018. The language of Section 7 appears to suggest that a party cannot be a bribe recipient if it is a counterparty in a transaction. It would hence be important to understand how a “transaction counterparty” would be interpreted to determine the scope of a bribe recipient under the AUCL 2018.

Narrow interpretations of “transaction counterparties” by Chinese law enforcement

The term “transaction counterparties” is not defined in the AUCL 2018. Neither has the Supreme People’s Court or SAIC published any official interpretation of the term yet. That said, various sources indicate that the enforcement agency tends to interpret the term “transaction counterparties” narrowly.

For example, Yang Hongcan, the director of SAIC’s Enforcement and Competition Bureau, reportedly commented in a newspaper interview that the phrase “transaction counterparty” should be interpreted as “actual” or “de facto” transaction counterparty. By way of illustration, Director Yang explained that if a school signs a purchase agreement with a school uniform company, the parties to this transaction should be the uniform company and all the students, who delegate the power to the school to buy uniforms on their behalf. Therefore, if the uniform company provides benefits to the school, which acts as an agent of the students, the act would constitute commercial bribery.

Such narrow or “de facto” approach of interpretation is further supported by some scholars’ “influencer” or “agent” theories. For example, Professor Xiao Jiangping, the chief of Beijing University’s Competition Law Research Centre, indicated in a public interview that the nature of the bribe recipient should be an entity or individual who can influence a transaction and who receives a benefit beyond the contractual price agreed upon by the transaction parties for influencing the transaction.

Whether public institutions are viewed as “transaction counterparties”

For business operators, especially those operating in an industry with relatively high risks from AUCL enforcement perspective, it is important to bear in mind the interpretation approach adopted by the enforcement agency when assessing the risks of certain practices. For example, would benefits provided to a public institution such as public hospitals or education institutions be viewed as commercial bribes?

To apply SAIC’s narrow interpretation, the answer is more likely to be Yes, as, for example, a public hospital may be viewed as an agent of its patients when entering into a contract, and the patients, rather than the hospital itself, are the de facto transaction counterparties that are excluded from the category of bribe recipients under the AUCL 2018.

Recent enforcement actions taken by some local AICs show a continuous focus on pharmaceutical companies’ dealings with hospitals. For example, after the AUCL 2018’s enactment (but before the amended law became effective), the Shanghai AICs took enforcement actions against multiple companies and issued administrative decisions, which seem to confirm that benefits provided to hospitals and/or their employees may constitute commercial bribery. A summary of these administrative decisions follows.

- On November 7, 2017, a district-level AIC in Shanghai imposed a fine of Rmb100,000 on a joint venture pharmaceutical company and confiscated its illegal gains over Rmb700,000 for sponsoring a doctor from a public hospital for his flight to attend an internal academic conference. The AIC decided that such act violated the PRC Drug Control Law which prohibits a drug manufacturer from providing benefits to the relevant personnel in a medical institute that uses its products.

- On November 22, 2017, the Shanghai AIC issued administrative penalties against a Chinese domestic pharmaceutical distributor by imposing a fine of Rmb180,000 and by confiscating the company’s illegal gains over Rmb11.4 million under the AUCL 1993. The Shanghai AIC decided that the distributor violated the AUCL 1993 by using company funds to provide benefits to multiple departments of a hospital and relevant hospital staff, including meeting sponsorships, meals, and gifts.

- On December 6, 2017, a district-level AIC in Shanghai fined a Chinese domestic medical device company Rmb100,000 and confiscated illegal gains over Rmb700,000, on the basis that the company provided medical devices to a hospital for free before selling machine consumables to the hospital.

Whether all off-the-book rebates or commission shall be treated as “commercial bribery”

The AUCL 1993 defines off-the-books rebates as commercial bribes, including hidden, falsified, or wrongly recorded discounts and commissions. However, the AUCL 2018 omits the provision prohibiting off-the-books rebates. The amended law only requires discounts and commissions be transparent and accurately recorded.

Some legal practitioners and commentators are of the view that commercial bribery requires a purpose of seeking transaction opportunities or competitive advantages. Given that transaction counterparties are no longer specified as potential bribe recipients, only off-the-books rebates to third parties to advance a business purpose may constitute commercial bribes. Some argue that although off-the-books rebates are not necessarily commercial bribes, they are important evidence for evaluating whether commercial bribes have been offered. It appears that by omitting the prohibition provision, the legislators intended to avoid punishing all off-the-books rebates. Further, they seem to want to distinguish payments which are genuine accounting mistakes from real commercial bribes.

Conclusion

While the AUCL 2018 has been effective since January 1, 2018, certain ambiguities and uncertainties still surround the amended law, including the definition of commercial bribery recipients. SAIC will likely issue implemental rules and regulations to address some of these questions. However, the contemplated restructuring of the State Council is expected to cause some delays of promulgation of the implementation rules and regulations.

Companies doing business in China should continue to closely monitor regulations and implementation rules to be issued by SAIC and its successor “State Administration of Market and Supervision.” In light of the all uncertainties and lack of clarifications as discussed above, companies are advised to hold a conservative opinion and to continue complying with the new changes introduced by the AUCL 2018 as well as the existing rules and guidelines adopted by SAIC and local AICs.

![]()

W: www.lw.com

E: hui.xu@lw.com

E: catherine.palmer@lw.com

E: tina.wang@lw.com

E: sean.wu@lw.com