Published in Asian-mena Counsel: Anti-Trust & Competition Special Report 2020

E: vasanth.rajasekaran@phoenixlegal.in

E: reshma.ravipati@phoenixlegal.in

Vasanth Rajasekaran and Reshma Ravipati of Phoenix Legal take a brief look at the Oyo, MakeMyTrip and Goibibo cases.

As we delve deeper into the age of the internet, the average individual’s dependence on internet-based service providers is also increasing by the day. In a bidding war to appease this ever-expanding customer base, we see service providers cropping up around every corner, taking businesses online, in most industries. Since this enables service providers to cut back on the costs incurred in providing the same service at a physical location, online services have proven to be far cheaper than the same services being provided in the physical domain. This has led to the creation of competitive imbalances in the physical and digital realm, thereby making it much harder for service providers in the physical domain to compete in the relevant market. Under these circumstances, it has become all the more difficult for the Competition Commission of India (CCI) to identify what practices deployed by online service providers constitute anti-competitive practices under the Competition Act, 2002 (Competition Act).

As we delve deeper into the age of the internet, the average individual’s dependence on internet-based service providers is also increasing by the day. In a bidding war to appease this ever-expanding customer base, we see service providers cropping up around every corner, taking businesses online, in most industries. Since this enables service providers to cut back on the costs incurred in providing the same service at a physical location, online services have proven to be far cheaper than the same services being provided in the physical domain. This has led to the creation of competitive imbalances in the physical and digital realm, thereby making it much harder for service providers in the physical domain to compete in the relevant market. Under these circumstances, it has become all the more difficult for the Competition Commission of India (CCI) to identify what practices deployed by online service providers constitute anti-competitive practices under the Competition Act, 2002 (Competition Act).

We have seen allegations of price-fixation being levied against Ola and Uber in the past, and numerous complaints against e-commerce giants such as Flipkart and Amazon; but more recently, focus seems to have shifted to the online hotel booking service sector as well. In 2019, two complaints (information) were filed with the CCI in relation to this sector. In both complaints, allegations with respect to abuse of ‘dominant position’ were levied against the opposite parties, among other ancillary anti-competitive practices that were sought to be highlighted. We will be analysing the orders rendered by CCI in both of these matters so far, and offer some insights on the manner in which we perceive the CCI seems to be treating complaints of this nature against online hotel booking service providers.

BACKGROUND

The RKG-Oyo Case1

A complaint was filed against Oravel Stays (Oyo), by RKG Hospitalities (RKG). The primary allegation levied against Oyo was that it had abused its ‘dominant position’ in the ‘relevant market’ to impose certain one-sided, unfair and discriminatory terms in its marketing and operational consulting agreement (Agreement) with RKG. Additionally, RKG also alleged that Oyo offered predatory discounts on hotel room bookings, and the conduct of Oyo was stated to be malafide, since its primary focus seemed to be to garner a high market share to the exclusion of other players in the ‘relevant market’, by creating unviable market conditions for its competitors.

The FHRAI Case2

The Federation of Hotel & Restaurant Associations of India (FHRAI) had filed information under Section 19(1)(a) of the Competition Act, alleging that MakeMyTrip India (MMT), Ibibo Group (Goibibo) and Oyo (collectively referred to as Opposite Parties) have entered into anti-competitive arrangements/agreements and have abused their ‘dominant position’ in the ‘relevant market’.3 In early 2017, the merger/combination of MMT and Goibibo was approved by the CCI (MMT-Goibibo).4 FHRAI submitted that this merger has facilitated their dominance in the ‘relevant market’ of OTA(s), and has empowered the two entities to operate in a manner independent of the competitive forces prevailing in the ‘relevant market’. FHRAI also alleged that Oyo’s unusually high market share in the ‘relevant market’ indicates that it has gained a competitive advantage and has secured a position of dominance in the ‘relevant market’.

DEFINING ‘RELEVANT MARKET’

DEFINING ‘RELEVANT MARKET’

The CCI reiterated that under the Competition Act, there are two dimensions to the term ‘relevant market’ viz. a ‘product/service’ dimension, and a ‘geographic’ dimension. The relevant product market is a culmination of all those products or services which are similar to the particular product or service in question, and are interchangeable or substitutable by the consumer, by reason of their similarity in characteristics, price and intended use. Consumer perceptibility with regard to interchangeability among products or services is said to be the most important parameter for defining the relevant product market.

In the RKG-Oyo Case, the CCI analysed the structure of the hospitality industry, to determine the relevant product market for Oyo. On one hand, there are online travel agencies (OTAs) such as MakeMyTrip, Goibibo, Yatra.com, Booking.com etc., which operate like aggregators that primarily facilitate bookings by connecting the hotels/properties with the end consumer. As aggregators, these OTAs use a variety of tools such as filters, directed searches, guest reviews and recommendations, and online payment options to provide a smooth and hassle-free booking experience to consumers. On the flip side, these aggregators offer a platform to various hotel owners to list their hotels on these aggregators’ apps, thereby making their hotels and properties that much more accessible to potential consumers. In return, these aggregators charge a commission from the hotel/property owners which may comprise a listing fee and/or a transaction fee, based on certain completed transactions using their services.

However, the CCI was of the opinion that Oyo did not qualify as an OTA. Oyo followed a franchise model, whereby standalone budget hotels partnered up with known brands such as Oyo, to take advantage of their brand value. Therefore, the CCI determined that what Oyo offers to these budget hotels is quite different from what an OTA offers. Oyo’s business relations with its partner hotels constitute a franchising service, comprising a bouquet of other services, which enables the franchisee hotels to reap the benefits of Oyo brand. Oyo in turn gets a commission or share in the revenues of its partner hotels, while assuring minimum monthly guarantee of revenues to such partner hotels.

Considering the discussion set out hereinabove, the CCI identified the relevant product market in the RKG-Oyo Case as “market for franchising services for budget hotels”, as opposed to “market for service providing budget hotels to customers through online booking”, as suggested by RKG. Further, since Oyo is a pan-India service and other partner hotels of Oyo are likely facing the same issues, the relevant geographic market was identified as the territory of India. The ‘relevant market’ was therefore demarcated as “market for franchising services for budget hotels in India”.

Relying on its decision in the RKG-Oyo Case, the CCI, in the FHRAI Case, held that the ‘relevant market’ for Oyo is different from the ‘relevant market’ for MMT-Goibibo, since Oyo is not an OTA. Accordingly, the ‘relevant market’ for Oyo was affirmed to be the “market for franchising budget hotels in India”, whereas the ‘relevant market’ for MMT, as well as Goibibo, both individually and taken together, was set out as “market for online intermediation services for booking of hotels in India”. Therefore, although the geographic element of the relevant markets was found to be the same for all the Opposite Parties, a distinction was observed in the product/service element of the relevant markets.

EXAMINATION OF ‘DOMINANT POSITION’

The CCI stated that the ability of an enterprise to behave independently of competitive forces and enjoy a ‘dominant position’ needs to be assessed in light of all relevant circumstances, as well as factors such as market share of the enterprise, size and resources of the enterprise, size and importance of the competitors, market structure and size of market, dependence of consumers on the enterprise etc., as detailed in Section 19(4) of the Competition Act.

Each and every case regarding allegations of abuse of ‘dominant position’ is unique, and needs to be assessed on its own merit, bearing in mind the characteristics of the ‘relevant market’. The CCI observed that since franchising is still an emerging trend in India, particularly in the budget hotel segment, a majority of budget hotels in India continue to operate as independent hotels. Furthermore, it observed that OTAs were responding to the emergence of budget hotel franchisers with new and more innovative ways of rendering their services, to try and compete with the value addition brought about by franchisers.

Therefore, given the stage of evolution of the ‘relevant market’ in the RKG-Oyo Case, the CCI deemed the emergence of hotel franchisers to be a catalyst for competition in the hotel industry as a whole. It was further of the opinion that although Oyo is a significant player in the ‘relevant market’, it cannot be unambiguously concluded that it holds a ‘dominant position’.

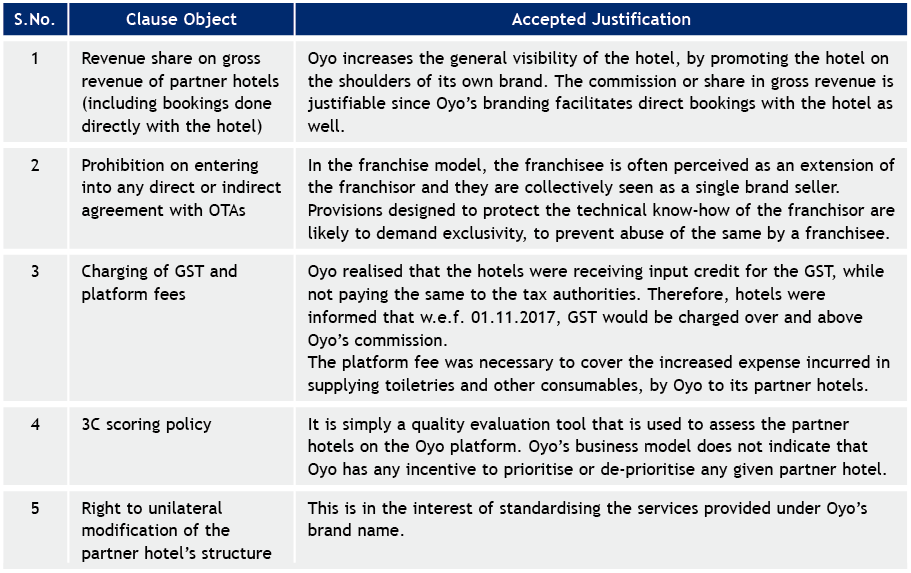

Even otherwise, it was concluded that Oyo’s conduct of business did not raise any red flags under the Competition Act, and the clauses alleged to be one-sided and discriminatory, in its marketing and operational consulting agreement, were also found to be justifiable in the context of its business model. A short snippet of the justifications accepted by the CCI in relation to each of such clauses has been provided hereinbelow.

On the other hand, in the ‘relevant market’ for MMT-Goibibo, it was observed that the two entities taken together as a group held 63 percent of domestic hotel online market share in 2017, as per their own investor presentation.5 Therefore, in the ‘relevant market’ for MMT-Goibibo, it appeared to prima facie enjoy a ‘dominant position’.

ROOM AND PRICE PARITY CONCERNS

FHRAI alleged that MMT-Goibibo has imposed a term in their contracts with partner hotels, prohibiting such partner hotels from selling their rooms on any other platform, or on their own online portal at a price below which they are being offered on MMT and Goibibo’s platforms. A room parity arrangement was also flagged by FHRAI, which allegedly restricted the inventory of rooms which a partner hotel could offer to OTAs other than MMT-Goibibo.

The CCI found the room and price parity restriction that was flagged by FHRAI, to be broad/wide in nature.6 The CCI was therefore of the opinion that analysis of restrictive clauses in a market should be done by evaluating whether such restrictive clauses lead to an enhancement of entry barriers, to the detriment of consumers in that market. Therefore, given the prima facie ‘dominant position’ of MMT-Goibibo and the inherent restrictive nature of the room and price parity clauses in question, it was determined that these clauses are required to be examined to gauge their impact under Section 3(4) and Section 4 of the Competition Act.

ANTICOMPETITIVE AGREEMENTS

ANTICOMPETITIVE AGREEMENTS

FHRAI drew the CCI’s attention to an agreement between MMT and Oyo (Oyo-MMT Agreement), which resulted in preferential treatment being accorded to Oyo properties on MMT’s website, and the removal of Fab Hotels and Treebo from MMT-Goibibo platforms on account of their refusal to pay an exorbitant brokerage/ commission which was sought to be charged from them. The possibility of exclusion of Fab Hotels and Treebo as a necessary result of the Oyo-MMT Agreement was also discussed, along with negative repercussions of the same on the ‘relevant market’. In consideration of the same, the CCI declared that the Oyo-MMT Agreement will also have to be carefully examined to assess its probable anti-competitive effect.

Parallelly, the CCI also indicated that the alleged deep discounting practices, predatory pricing policies, discriminatory levy of service fee on certain hotels, and justifications offered by MMT-Goibibo for delayed delisting and misrepresentation of availability information of hotels which have opted to disassociate themselves with MMT-Goibibo may also be looked into by the Director General at the time of investigation, along with the aforementioned broader issues.

Having recorded the abovementioned observations and preliminary findings, the CCI directed the Director General to carry out a detailed investigation into the matter, in the FHRAI Case, in terms of Section 26(1) of the Competition Act. This probe is currently underway, and a report of the same is yet to be submitted to the CCI, by the Director General.

CONCLUSION

The CCI seems to bear an open mind towards novel services and service providers emerging as a result of technological advancements. Both OTAs and budget hotel franchisers are recent entrants in the hotel industry, although the former is relatively older than the latter. The trend observed in previous years in the CCI’s approach towards complaints against such new entrants, even with respect to the e-commerce industry, has been to extend some leeway to new players offering innovative services in the digital market of any given industry, until they find their footing. This is largely the same approach that has been reproduced by the CCI in dealing with Oyo.

During their emerging stages, digital market players are seen as competition inducing and fostering elements, which are beneficial to the relevant industry. However, when the service matures with time and the policies of such digital market players become more identifiably anti-competitive in nature, as is perceived to be the case with MMT-Goibibo, the CCI intervenes and re-assesses the policies put in place by such entity/entities. Under these circumstances, everything starting from the business model of the entity/entities under scrutiny, to individual agreements of such entity/entities with the other market players may be called up for careful examination and investigation. It is therefore imperative for market players to consciously avoid implementation of policies that may tread on the lines of anti-competitive practices, to avoid the consequences of being flagged for violation of provisions of the Competition Act.

______________________________

1. Case No. 03 of 2019, dated 31 July 2019, available at:

https://www.medianama.com/wp-content/uploads/oyo-cci-order.pdf.

2. Case No. 14 of 2019, dated 28 October 2019, available at:

https://www.cci.gov.in/sites/default/files/14of2019_0.pdf.

3&4. Under Section 3 and Section 4 of the Competition Act, 2002.

5. The CCI rejected MMT-Goibibo’s contention that other players such as PayTM, HappyEasyGo, and Thomas Cook have been posing competitive constraints on them, as none of these entities appeared to have any significant market presence in the relevant market.

6. The CCI stated that restrictions may be categorised as ‘narrow’ restrictions and ‘wide’ restrictions. A narrow restriction, is when a supplier is asked to not set lower prices or offer better terms through their own websites, in comparison to prices/terms offered on the OTAs platform. A wide restriction, on the other hand, is when an OTA restricts a supplier from charging lower prices or providing better terms on their website, as well as through any other sales channel, including other OTAs.

______________________________

E: vasanth.rajasekaran@phoenixlegal.in

E: reshma.ravipati@phoenixlegal.in

![]() Click Here to read the full issue of Asian-mena Counsel: Anti-Trust & Competition Special Report 2020.

Click Here to read the full issue of Asian-mena Counsel: Anti-Trust & Competition Special Report 2020.