On July 30, 2021, the Central Administrative Court rendered its verdict against, among others, the Director of Wattana District, Bangkok Metropolis; the Governor of Bangkok Metropolis; and the Governor of the Mass Rapid Transit Authority of Thailand, revoking all governmental authorizations with respect to the construction of Ashton Asoke Condominium Project.

Such verdict has had an immense impact on the developer of such condominium project, Ananda Development PCL (SET: ANAN), one of the most reputable Stock Exchange of Thailand-listed real estate developers, that has developed many well-established condominium brands, such as Ashton, Ideo, Ideo Mobi and Elio, and has also inevitably raised several questions for Ananda’s customers who have purchased condominium units in Ashton Asoke Condominium Project.

Therefore, we would like to take this opportunity to analyze such verdict and flag certain key takeaways and debatable issues, while we await the final result of one of the landmark real estate-related lawsuits in Thailand.

Issue

Does Ashton Asoke Condominium Project (the “Project”) comply with Section 2, paragraph 2 of the Ministerial Regulation No. 33 (B.E. 2535 (1992)) Issued by Virtue of the Building Control Act B.E. 2522 (1979) (the “Ministerial Regulation No. 33”), as interpreted by the Central Administrative Court (the “Court”)?

Underlying Rule

Section 2. paragraph 2 of the Ministerial Regulation No. 33 (the “Underlying Rule”) requires that at least a single side (with at least 12 meters in length) of the “site area” on which a high-rise building or an extra-large building (in each case, with gross floor area of greater than 30,000 square meters) is situated be adjacent to a “public road” with the boundary width of at least 18 meters, and such public road must connect to another public road of the same or greater boundary width whereby the boundary width of the connection between the two public roads must not be less than 18 meters at any point.

In essence, from the Ministerial Regulation No. 33:

1) “site area” means the area of a plot of land (i.e., represented by a single land title document) or plots of land (i.e., represented by multiple land title documents) submitted to the competent authority for the construction of a building

2) “public road” means a road into or through which the general public may enter or pass, in each case whether with or without a fee.

Key Facts Heard and Key Questions Raised by the Court

Key Facts Heard by the Court |

|

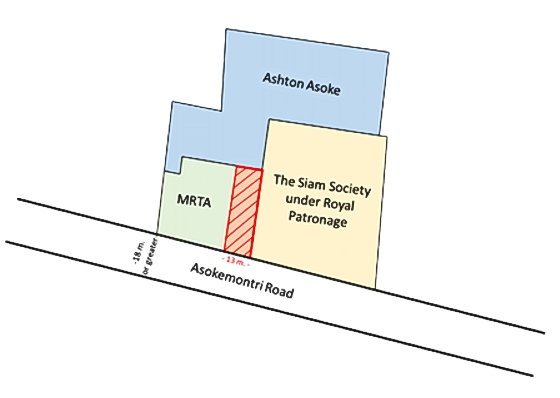

1) The Project qualifies as an extra-large building with the gross floor area of greater than 30,000 square meters. Therefore, the Underlying Rule applies to the Project. Figure 1: Disputed Site Area and its surrounding areas

2) As depicted above, the “Disputed Site Area” (i.e., the red rectangular block) serves as the sole connection between the Project’s site area and Asokemontri Road (i.e., a public road with the boundary width of 18 meters or greater), and the Disputed Site Area belongs to the Mass Rapid Transit Authority of Thailand (“MRTA”). 3) In around 1996, the Disputed Site Area was expropriated from its private owner for the benefit of the Metropolitan Rapid Transit Authority. Then in 2000, by Section 88 of the Mass Rapid Transit Authority of Thailand Act B.E. 2543 (2000) (the “MRTA Act”), the Metropolitan Rapid Transit Authority transferred ownership over the Disputed Site Area to MRTA. 4) Ananda Development PCL (through its subsidiary) (the “Developer”) acquired the plots of land for the construction and development of the Project in early 2014. 5) On June 26, 2014, MRTA and the Developer entered into an agreement on the use of the Disputed Site Area owned by MRTA as the access to and exit from the Project (the “MRTA Agreement”). 6) Pursuant to the MRTA Agreement, in exchange for the remuneration agreed between MRTA and the Developer, MRTA allows the Developer to use the Disputed Site Area as the access to and exit from the Project. According to the same Agreement, the side of the Disputed Site Area which is adjacent to Asokemontri Road is approximately 13 meters long. 7) On July 4, 2014, MRTA issued to the Developer a consent letter which provides MRTA’s consent for the Developer to use the Disputed Site Area for the construction of the Project (the “Consent Letter”). Entailed in the Consent Letter is the condition that MRTA reserves its unilateral rights to change or alter the position of the access to and exit from the Project (as currently located in the Disputed Site Area) and to reduce the current size of the area on which the access/exit is located (which includes the reduction of the area of the Disputed Site Area), for which in each case the Developer would not be entitled to any damages (such condition, the “Key Condition on the Use of the Disputed Site Area”). 8) On or around February 23, 2015, the Developer submitted the Consent Letter to the competent authority for the commencement of the construction of the Project. |

Key Questions Raised by the Court

1) Does the Disputed Site Area legally constitute a public road under the Ministerial Regulation No. 33?

2) Does the Disputed Site Area legally constitute a part of the Project’s site area under the Ministerial Regulation No. 33?

Key Findings of the Court

1) The Disputed Site Area is NOT a public road.

The Court found that the Key Condition on the Use of the Disputed Site Area clearly reflects MRTA’s intention that MRTA merely allows the Developer to use the Disputed Site Area as the Project’s access and exit (which connects the Project to Asokemontri Road), without any intention of MRTA to allow the general public to enter into or pass through the Disputed Site Area. Therefore, the Disputed Site Area does not qualify as a public road under the Ministerial Regulation No. 33.

2) The Disputed Site Area is NOT a part of the Project’s site area. As such, the Project does NOT comply with the Underlying Rule because NO side of the Project’s site area (with at least 12 meters in length) is adjacent to Asokemontri Road.

The Court concluded that the Disputed Site Area cannot serve as a part of the Project’s site area under the Ministerial Regulation No. 33 for the following key reasons.

- The Disputed Site Area was expropriated from its private owner for the benefit of the Metropolitan Rapid Transit Authority for the construction of the first phase of the Metropolitan Rapid Transit (MRT) Project, and in capacity as the transferee of the Disputed Site Area under the MRTA Act, MRTA is legally bound by such purpose of the expropriation.

- Sections 7 and 9 of the MRTA Act obligate MRTA to carry out only activities which relate to the “mass rapid transit business”. However, MRTA’s consent provided to the Developer through the Consent Letter for the use of the Disputed Site Area in favor of the Project (which is a condominium project) indicates that the Disputed Site Area would be “permanently” used as the Project’s access and exit. This is because the Disputed Site Area serves as the sole connection between the Project’s site area and Asokemontri Road. Such consent of MRTA intrinsically favors the business operation of the Developer.

- Despite the remuneration payable to MRTA under the MRTA Agreement, the Court views that MRTA’s use of the Disputed Site Area in accordance with the MRTA Agreement and the Consent Letter does not qualify as use of the Disputed Site Area for or in the interest of the mass rapid transit business. Therefore, MRTA’s entry into the MRTA Agreement and provision of the Consent Letter breaches Sections 7 and 9 of the MRTA Act. Accordingly, the Consent Letter is illegal.

- Given the illegality of the Consent Letter, it logically follows that: (i) MRTA does not allow the Developer to use the Disputed Site Area as the Project’s access and exit; and as such (ii) the Disputed Site Area does not qualify as a part of the Project’s site area under the Ministerial Regulation No. 33.

Without the Disputed Site Area as a part of the Project’s site area, there is no side of the Project’s site area (with at least 12 meters in length) adjacent to Asokemontri Road. Therefore, the Project does not comply with the Underlying Rule.

3) The Court has revoked all governmental authorizations authorizing the construction of the Project with retroactive effect.

Because the Project does not comply with the Underlying Rule in the Court’s view, the Court has revoked all governmental authorizations which relate to the construction of and modification to the Project with retroactive effect. That is, all such governmental authorizations have been deemed by the Court to have been revoked with effect from their respective inceptions.

Key Takeaways – Angles to Consider

There will be a long road ahead before we see the final judgment by the Supreme Administrative Court, as the Developer is certainly appealing the Court’s findings to the Supreme Administrative Court. In the meantime, with all due respect to the Court, we think it would be helpful to flag certain debatable issues stemming from the Court’s findings for constructive debates among people interested in this landmark lawsuit (whether with or without a background in legal education or practice).

1) Is there a possibility for the Disputed Site Area to become a public road under the Ministerial Regulation No. 33?

If the MRTA Agreement and the Consent Letter were to be amended in a way that (i) the Key Condition on the Use of the Disputed Site Area is omitted and (ii) reflected MRTA’s intention for the Disputed Site Area to be used by the general public as a public road (whether with or without a fee), would the Disputed Site Area become a public road under the Ministerial Regulation No. 33?

If so, one side of the Project’s site area (of at least 12 meters in length) would then be adjacent to a 13-meter-wide public road (i.e., the Disputed Site Area), which would connect the Project to Asokemontri Road. Even though this would not yet satisfy the Underlying Rule because the Project’s site area would need to be adjacent to an 18-meter-wide public road, it might be possible for MRTA and the Developer to agree to extend the area of the Disputed Site Area such that the Disputed Site Area would qualify as an 18-meter-wide public road under the Ministerial Regulation No. 33.

However, if the foregoing option were to be taken into MRTA’s and the Developer’s consideration, MRTA would also need to justify why MRTA allowing the Disputed Site Area (as extended into an 18-meter-wide road) to be used as a public road under the Ministerial Regulation No. 33 would fall within the ambit of Sections 7 and 9 of the MRTA Act. That is, MRTA would need to justify how such permission would relate to or benefit the mass rapid transit business.

2) Is there a possibility for the Supreme Administrative Court to view that the Disputed Site Area should instead qualify as a part of the Project’s site area?

The cornerstone of the Court’s revocation of all governmental authorizations authorizing the construction of the Project is its finding that MRTA’s Consent Letter given to the Developer is illegal, because MRTA is not authorized by the MRTA Act to carry out any activity which does not relate to the mass rapid transit business. However, having a closer look at Section 7 of the MRTA Act, which enumerates the objectives of MRTA (in its capacity as a juristic person), one may interpret the extent of such objectives in a broader manner relative to the Court’s interpretation of the same.

Section 7(3) of the MRTA Act provides that MRTA may carry out a business relating to the “mass rapid transit business” and other businesses in the interest of MRTA and the general public for the use of the mass rapid transit business. From Section 4 of the MRTA Act, the “mass rapid transit business” means construction, expansion, restoration, improvement, repair and maintenance of mass rapid transit system, train operation, provision of car park, services, facilities and other operations in relation to such business.

Currently, the MRTA-owned area adjacent to the Disputed Site Area (i.e., the light-green block in Figure 1 above as remarked with MRTA) serves as parking spaces for MRTA’s monthly customers. Accordingly, not only does the Disputed Site Area serve as the Project’s access and exit, but the Disputed Site Area also serves as the access and exit of the MRTA-administered parking spaces which connects the parking spaces to Asokemontri Road. Given the actual condition of the Disputed Site Area and such adjacent parking spaces, one could find that, in practice, MRTA has properly utilized the Disputed Site Area and the parking spaces area, and that MRTA could have done nothing further to make the most of the Disputed Site Area. Therefore, MRTA’s concurrent use of the Disputed Site Area as the access and exit of each of the MRTA-administered parking spaces (which should fall within the ambit of the mass rapid transit business) and the Project (which provides the remunerations for MRTA) could, perhaps, be the most viable and practical option for MRTA to avail itself and make the most of the Disputed Site Area.

If the Supreme Administrative Court were to be convinced by the foregoing conceptual idea, it would still be possible for the Supreme Administrative Court to overturn the decision and to find that the Consent Letter was made in the interest of MRTA and the general public for the use of the mass rapid transit business. If so, the Consent Letter would not be illegal, and accordingly, the Disputed Site Area could legally constitute a part of the Project’s site area.

In such hypothetical scenario, the Disputed Site Area would serve as one side of the Project’s site area (of at least 12 meters in length) adjacent to Asokemontri Road, because the Disputed Site Area is 13 meters wide. Thus, the Project would comply with the Underlying Rule.

3) If ultimately the Disputed Site Area does not qualify as a part of the Project’s site area, would demolition of the Project be the “single consequence”?

In this scenario, the Developer would still have an opportunity to fix the Project’s incompliance with the Underlying Rule. This is because the Building Control Act B.E. 2522 (1979) conceptually provides that no demolition of any illegally constructed building should take place until there ultimately is no possible solution to fix the illegality thereof.

Therefore, strictly from a legal perspective, for example, it might still be possible for the Developer to acquire a part of the plot(s) of land on which The Siam Society under Royal Patronage is located, such that the part acquired could serve as a part of the Project’s site area which would be adjacent to Asokemontri Road. Then, the Project would comply with the Underlying Rule.

However, if the demolition of the Project turned out to be the sole option for the Developer, the consequences thereof (especially the impacts against the owners of the condominium units of the Project) could be unprecedentedly (and perhaps, unimaginably) detrimental to both the Developer of the Project and the owners of the condominium units.

4) What is a key takeaway from a customer’s perspective?

It would not be an understatement to say that the key issues stemming from this lawsuit have presented an “inconvenient truth” to every real estate customer (especially a condominium buyer).

Normally, most individual buyers (including some corporate buyers) of real estate properties do not feel the need to conduct a legal due diligence investigation on each real estate property that they are looking to buy. As a result, they would not be aware of legal exposures or risks they incur or may have incurred. Therefore, in an abundance of caution, this might be an opportune moment for all real estate buyers (including individual buyers) to start considering engaging a professional firm (with proven local expertise who can offer an economical and cost-effective budget) to help identify exposures or risks presented by each prospective real estate property.

Our Real Estate Team will continue to follow closely on the progress of this landmark case. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact the authors.

|

Kudun Sukhumananda

Partner |

|

Peerasanti Somritutai

Senior Associate |

|

Chavisa Jinanarong

Associate |