Last week’s update suggested that the standard explanations for the current financial volatility don’t really add up. This week’s lays out the mechanics of an alternative explanation: that the world’s financial markets are struggling to absorb the impact of the US dollar’s strength.First, though, to recap last week’s conclusions: i) Current global monetary conditions don’t suggest the world economy is likely to plunge into recession, and globally, domestic demand data remains relatively robust. In particular, labour markets remain strong in the US and UK, are clearly improving in the Eurozone and also in Northeast Asia (outside China). ii) Within the private sector, there has been no noticeable credit cycle, and no bubble-like investment cycle, which invites or requires re-winding. iii). Although oil prices are falling, this reflects a supply-glut caused by attempts to resist a historic unwinding of the OPEC monopoly, rather than a shortfall in demand. (In fact, OPEC’s global demand figures suggest world demand rose by 1.9 percent in 2015, up from 1.5 percent in 2014 and one percent in 2013, although they expect a moderation to 1.3 percent in 2016.) Rather, the key to the current volatility, and also to China’s ‘capital flight’ lies somewhere else: specifically, it has its roots in the dollar going on a tear between the middle of 2014 and early 2015. Between July 2014 and March 2015, the currency rallied 12.2 percent against the IMF’s basket currency, the SDR. Money suddenly got more expensive. The widest-angle view of the US dollar helps explain why its movements matter so much: the dollar is the world’s currency, and when you see it strengthen, it means the value of money has just gone up. But now narrow it down to the company level. Imagine your company has borrowed in US dollars to fund a new machine, and the US dollar has just risen against the currency of a major competitor. Tomorrow you find your competitor has dropped his US dollar selling price, so you face the choice of cutting your price or losing market share. Either choice cuts into your profits and cashflow, and that makes it tougher to make your interest payments. What’s worse, your banker knows this, and feels just a little less friendly to you than he was last week. Don’t be too hard on him though, because the chances are that the bank’s own US dollar-funding opportunities are also shrinking. After all, his own earnings have also just fallen in US dollar terms. This is what happens when the value of money rises. A rising US dollar provided the background to Asia’s financial crises in 1997 and 1998, with the yen falling 33 percent against the US dollar between June 1995 and April 1997 (from 84.5 to .125.5 to the US dollar). At the time, Japan accounted for just over half of all NE Asia’s exports, so as Japan dropped its prices, everyone else did too. Also, the background to the 2000/2001 US recession was a strengthening of the US dollar, which rose 16.2 percent against the SDR between October 1998 and mid-2001. Today’s worries have once again been crystallised by the strength of the US dollar. This time the stress is less to do with export prices and more to do with a loss of funding opportunities. Yes, globally manufacturers felt the chill of deflation; but Asia’s export economies are cushioned not only by the margins relief of falling commodity prices, but by the huge foreign exchange reserves, which are the prize won by the private sector running persistent sector savings surpluses. When the US dollar started rising in July 2014, China had US$3.966 trillion in foreign reserves, and Asia excl. China had a further US$2.983 trillion. China decided the Rmb would remain effectively pegged to the US dollar even as it rose. This caused, and is causing, some pain. But in truth, the pressure on export was not decisive – as sustained trade surpluses and the global resilience of domestic demand attests. The tougher impact came from the impact on capital flows. The rise in the US dollar reminded the world’s banks of ‘what happened last time’ and they set about cutting credits to those perceived vulnerable (including each other).The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in Basel tracks cross-border lending, and although its quarterly reports are slow to appear, they tell a very clear tale. Between September 2014 and September 2015, foreign lending into the US fell by US$321 billion, into the UK fell US$544 billion, and by US$83 billion into both France and Germany. In all, that’s a fall of just over US$1 trillion in cross border lending into the major financial capitals of the work during the 12 months to September 2015. Asia’s international finance centres were hit too: cross-border lending into Singapore dropped by US$67.4 billion (or 11.1 percent) and lending to Hong Kong fell by US$19 billion (or by 3.1 percent), But the worst hit of any country was China, where cross border lending fell by 20.9 percent year on year, or by US$231 billion in the 12 months to September 2015. During the same period, China’s foreign exchange reserves fell by US$374 billion. So it It this net repayment of cross-border debt which accounts for the majority of China’s alleged ‘capital flight’. |

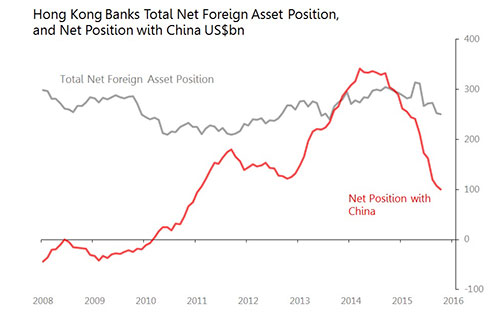

When it comes to lending into China, Hong Kong plays a special role – and the HKMA produces its data (slightly) faster than the BIS. HKMA’s data tells us that Hong Kong’s net lending to China fell from US$333 billion in September 2014 to just US$100 billion by October 2015. On those trends, net lending into China by Hong Kong will have fallen to around US$50 billion by end-January, and will have been all squared away by April. Most likely, however, the pace at which lines have been pulled will have quickened over the last few months.This pulling of banking lines to China does seem to be the fundamental force skinning China of its foreign reserves. But if so, it has two important consequences. First, when all the credit lines are pulled, the pressure on China is likely to ease: as far as Hong Kong’s position is concerned, we’re probably nearly there already. And second, it means we must re-think those tales of China’s ‘capital flight’, which will be next week’s topic. Michael Taylor runs Coldwater Economics, a consultancy serving institutional investors worldwide since 2009. Michael spent 15 years of his career in Asia, principally Hong Kong and Tokyo, as Asia economist for Morgan Stanley and chief economist for W I Carr. He offers a daily Shocks & Surprises services which tracks approximately 450 economic data releases each month, identifying and briefly explaining those which deviate significantly from consensus or trend. For more information: |