Fed chairman Janet Yellen’s dovish comments after the Fed’s FOMC meeting persuaded the market that we can expect only two US rate hikes this year, rather than four. Mrs Yellen attributed the Fed’s dovish turn to the feared impact on the US economy of negative economic and financial developments elsewhere in the developed world.In fact, the justification for monetary indulgence lies nearer to home, since the US’s return on capital indicator has already peaked, and this is likely to dampen capex ambitions for the time being. The Fed’s outbreak of caution can also, however, be seen as official confirmation of the regime change which halts and probably reverses the combination of strong dollar, weakening commodity prices and crippled cross-border financial flows, which has been the principal challenge of the last 18 months. That regime change began to emerge as early as mid-December, when the dollar broke out of its strengthening trend. But the signs got clearer in February, particularly as Asia’s foreign exchange reserves began to rise once again, having been under the cosh since 2H14. Among Asian economies, no country stands to benefit more clearly than Indonesia. The case for Indonesia was also bolstered by February’s surprisingly large trade surplus, which consolidates the chances that the country is finally breaking into private sector savings surplus once again. Last week we learned February’s exports fell only 7.2 percent yoy with a monthly gain 1.5SDs above historic seasonal trends: within that, oil & gas exports fell 36.5 percent yoy, but non-oil & gas exports fell only 2.2 percent yoy and were 1.4SDs better than trend. February’s US$1.137bn trade surplus, meanwhile, was the largest since December 2013. This improved trading performance raises the possibility – no more – that Indonesia might show a modest private sector savings surplus in 1Q16, the first since 1Q12. All the usual caveats and more apply, but current trajectories, if maintained, point that way. If Indonesia does indeed break into savings surplus, it signals a fundamental reversal in how cash flows around that economy. Specifically, the private sector begins to deliver cash back into the financial system, rather than taking cash from it. As a result, Indonesia’s own banking system will, of necessity, be net buyers of government bonds, which will pull down bond yields. This is precisely the sort of news which gets noticed by emerging market investors. |

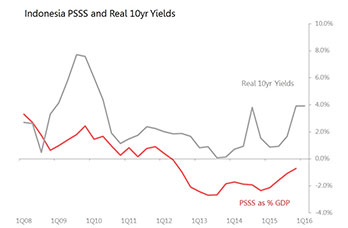

Bank Indonesia held its own policy meeting last week too, which cut the base rate by 25bps to 6.75 percent, with the deposit and lending facility rates falling to 4.75 percent and 7.25 percent respectively. It clearly had room to do so: although February’s 4.4 percent yoy CPI result was on the upper side of one percent above or below four percent target, the current trajectory will take it comfortably below four percent in 3Q and threatening the lower band by year-end. Even if the currently improving trajectory is replaced by trend rates of inflation, there’s no short or medium term likelihood that inflation will breach five percent during the next 12 months.Prior to BI’s decision, Indonesia’s 10yr bond yields looked very generous at 7.85 percent. The underlying dynamic has been perverse during the last two years, with nominal bond yields getting absolutely no benefit from the improvement in Indonesia’s underlying private sector savings balance. Rather, yields stayed around eight percent even as the private sector savings deficit narrowed from 2.7 percent of GDP in mid-2013 to just 0.7 percent by end-2015. As a result, real yields of 3.9 percent are now the highest since mid-2010. Don’t expect them to stay like that. For more information: |