An in-house legal team can achieve much more than saving money, but it requires a more strategic approach than most companies have adopted, writes Mitchell Kowalski, the Gowling WLG Visiting Professor in Legal Innovation at the University of Calgary Law School.

An in-house legal team can achieve much more than saving money, but it requires a more strategic approach than most companies have adopted, writes Mitchell Kowalski, the Gowling WLG Visiting Professor in Legal Innovation at the University of Calgary Law School.

The years since the beginning of the 21st century have seen an explosion in the number of in-house counsel across the globe. The Association of Corporate Counsel has more than 43,000 members in 85 countries employed by over 10,000 organisations; the Corporate Legal Operations Consortium boasts thousands of legal operations personnel; and of course the In-House Community has over 20,000 members with responsibility for legal and compliance issues in the Asia-mena region.

The in-house field is now exceptionally large and it should be no surprise that there is a direct correlation between the rising costs of outside counsel and the growth in in-house legal teams. It’s cheaper to simply build an in-house team than to rely upon outside counsel for great swathes of corporate legal work. And that is the predominant strategy used by general counsel around the world. But is it a long-term solution, or merely a short-term labour arbitrage play?

to simply build an in-house team than to rely upon outside counsel for great swathes of corporate legal work. And that is the predominant strategy used by general counsel around the world. But is it a long-term solution, or merely a short-term labour arbitrage play?

In my view, building an in-house team and expecting that tactic to solve all your legal woes is overly simplistic. Ideally, the legal function of any corporation should, among other things: enable better strategic sourcing of external suppliers; inform management processes to control the delivery and cost of legal work (internally and externally); highlight non-legal work being done by the legal department that may be handed back to the business; enable a continuing strategic overview as to the shape and size of the internal legal department; and create management information for the legal team.

Creating a behemoth legal department doesn’t address many of these items. Nor does asking outside law firms to come up with some ideas on their own. Casey Flaherty, an American consultant and commentator, has pointed out in a number of blogs and talks that outside lawyers are often truly befuddled by RFP questions such as: “What innovations will you use to create added value for us?” In many cases, according to Casey, firms tend to answer with some variation of: “We upgraded to Windows 10.”

In-house counsel who want a truly client-centred, unique and innovative solution to their “more for less” challenge will have to come up with it themselves.

What is needed is a new approach to how in-house legal departments operate, and how they view their role — an approach that sits somewhere between the “build a giant in-house team” idea and the unhealthy “in-house versus outside law firm” tension that I often see in the marketplace. There has to be a third way that meets the goals of in-house counsel while also being manageable and cost-effective. Alvin Toffler’s 1980 bestseller, The Third Wave, was based in part on the premise that major business breakthroughs come not from single, isolated technologies, but from imaginative juxtapositions, developed through large-scale thinking and the application of general theories. In other words, breakthroughs come from moving the existing pieces of the puzzle around in a way that not only achieves the desired result, but also leaves room for future changes.

True sustainable innovation in the context of in-house legal departments is not simply jumping on to the newest technology (although technology may form a part of innovation), but rather the careful integration of the in-house team, outside providers and the business units under the umbrella of a master strategy that aligns with the corporation’s values and goals. Few in-house departments think in these terms, mostly because they’re too busy dealing with the work that seems to unceasingly flow to them each day.

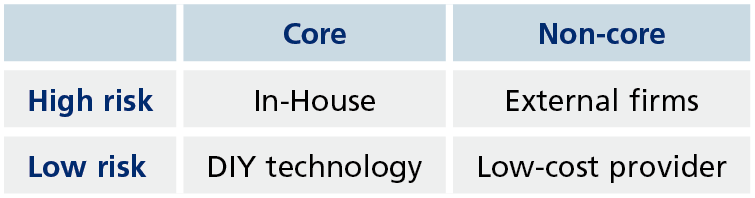

So let me suggest a simple framework to help in the creation of an innovative master strategy — one that is based on achieving legal service balance. A corporation is out-of-balance when its legal service needs are not aligned with the skills and costs of its providers (both internal and external). Legal service imbalance not only results in corporations over-paying for legal services or underutilising legal skills, it also adversely affects customer satisfaction of the business units, as well as the job satisfaction and engagement of those on the internal legal team. Some corporations, such as the American operations of Cisco Systems, assess legal service imbalance through a core/risk matrix (based on level of risk and connection to the core business of the corporation) that incorporates some of the principles of Design Thinking (start with empathy/understanding) and Lean (ensure the right people are doing the right tasks). The ultimate goal is to achieve perfect alignment of legal resources with both risk to the corporation and the corporation’s core business.

The matrix is divided into the following four quadrants:

- Legal work that is high risk to the corporation and also core to the corporation’s business should be the only work that the in-house legal team deals with. As this work represents the highest and best use of internal legal talent, it should result in higher employee satisfaction and better employee engagement.

- Legal work that is high risk and not core to the corporation’s business should be the only work done by external law firms. This capacity and expertise is not required by the in-house team.

- Legal work that is low risk but not core to the corporation’s business should only be done by a reliable low-cost provider with appropriate playbooks and quality control. This work is fairly repetitive, not continuing, and does not require a high level of legal skill. This work also has some tolerance for slight imperfections. The recent EY and Riverview Law tie-up is an indication of the number of quality options in this area for in-house teams.

- Legal work that is low risk but core to the corporation’s business is typically well-suited for a DIY technology solution (such as an expert system) used directly by the business teams with little or no involvement from the internal legal team. This work is repetitive, does not require high levels of legal skill and has some tolerance for slight imperfections; but it’s continuing and needs to be done quickly and efficiently. Australian-based Wesfarmers’ use of Neota Logic to automate its non-disclosure agreements is a great example of this.

But that is just the beginning. A strategy of innovative optimisation can then be instituted in each quadrant with the goal of not only continuously improving operations, but also of engaging the business units and empowering the internal legal team. For example, in connection with the High risk/Non-core quadrant, a corporation can initiate a disciplined/rigorous selection process to create new pricing models that reward valuable behaviour and penalise undesirable behaviour, all with clear, measurable key performance indicators. New technology may or may not form part of this approach. The selection process may involve an RFP or it may involve negotiations with a few select providers; the key is for this model to be a win-win for both parties, which requires the internal legal team to spend a great deal of time clearly and precisely defining the behaviour and outcomes that it values. American-based Wolverine used this approach quite successfully for its trademarks portfolio with law firm Seyfarth Shaw.

At a minimum, each quadrant will require:

- Someone on the internal team to lead, and be accountable for, innovation within that quadrant.

- Internal legal team leadership must continually walk-the-talk of innovation and continuous improvement to signal its importance to team culture and to the master strategy.

- Members of the internal team and the business units must be empowered to make suggestions (without fear of ridicule or repercussion) and be given clear direction as to how those suggestions are to be made.

- A transparent, disciplined and unbiased evaluation process must be created for all suggestions.

- Suggestions that are acted upon and that achieve success should be celebrated widely and rewarded.

Unfortunately, the space requirements of this article only allow for a very high-level explanation of the two-step process involved in creating a more innovative strategy for operating an in-house legal department. This strategy and executing on it will require a large time commitment that goes beyond the day-to-day work load. It also requires strong, focused leadership and may also benefit from outside assistance, which may explain why the simple “build a giant in-house team” approach is so pervasive globally. But is that approach really adding value for shareholders and business units? And is it providing a rewarding career for the internal legal team?

Twitter: @mekowalski

Email: mekowalski@kowalski.ca